Growing up near and then in Berkeley, I got used to the traffic barriers and speed bumps that dot the residential side streets not far from downtown and the university campus. I’ve heard people unfamiliar with the area complain about the inconvenience they cause drivers trying to get across town, but my parents knew where to turn to avoid getting dead-ended. That was sort of the point: keeping passers-through on the major streets and non-local traffic off the smaller ones.*

Today I see that some of the counties outside DC have been adopting similar tactics for similar reasons. The Post report makes it sound like a war:

Scores of commuters were using Southampton Drive in Kings Park every day to cut between Rolling and Braddock roads and avoid several stoplights and bumper-to-bumper congestion. The community petitioned for and added speed humps every block or so. The humps were followed by four-way stop signs, a 15-mph speed limit and concrete “bump-outs” that make the road seem narrower and cut speeds.

Drivers stopped using Southampton but switched to parallel Eastbourne Drive. The community took the unusual step of installing a concrete barrier to prevent a right turn onto Eastbourne. A “Do Not Enter” sign made it even more daunting.

So drivers took a left off Southampton and used Kings Park Drive. The community responded with more speed humps and speed restrictions. Then it brought out the heavy artillery: traffic circles.

I believe that’s in Fairfax county. Here’s Montgomery County:

Chevy Chase and Bethesda have learned to combat cut-through artists by making it nearly impossible to get from Massachusetts Avenue to Wisconsin or Connecticut avenues via neighborhoods. Once-tempting streets now have an array of signs with so many prohibitions that drivers sometimes have to pull over to figure out whether and when to turn.

Signs at Bradley Boulevard and Kennedy Drive (an alluring alternative to the parallel, choked Little Falls Parkway) prohibit left or right turns during rush times. And trucks and buses weighing more than three-quarters of a ton can’t drive through. However, the signs specifically allow emergency vehicles on Kennedy Drive’s precious pavement.

Nancy Floreen, a Montgomery County Council member, said the county “wins the world prize on the footnotes we have on our street signs, like ‘No right turn when the moon is full’ sort of thing.”

There have been real benefits –

Sharon S. Bulova, the Fairfax County supervisor who represents Kings Park, said the neighborhood’s efforts reduced cut-through traffic by 60 percent.

“It really saved the community,” Bulova (D-Braddock) said. “They used to have cars ending up on lawns trying to take a curve too fast. Parents were fearful for kids and pets. People were in a hurry and in commuter mode.”

– but escalation is not without its costs:

Still, in some neighborhoods, even residents complain about living around so many restrictions, Floreen said.

Tracey Hughes of Somerset lives just off Dorset Avenue, which has the full complement of traffic humps, rumble strips, stop signs, crosswalk signs, electronic speed monitors and four-way stop signs at every block.

Hughes, who has lived in the neighborhood for six years, said the street doesn’t appear to have too much traffic. But, she said, she assumes town leaders know what they are doing by installing the driving disincentives.

These battles might not stop unless something changes the terrain:

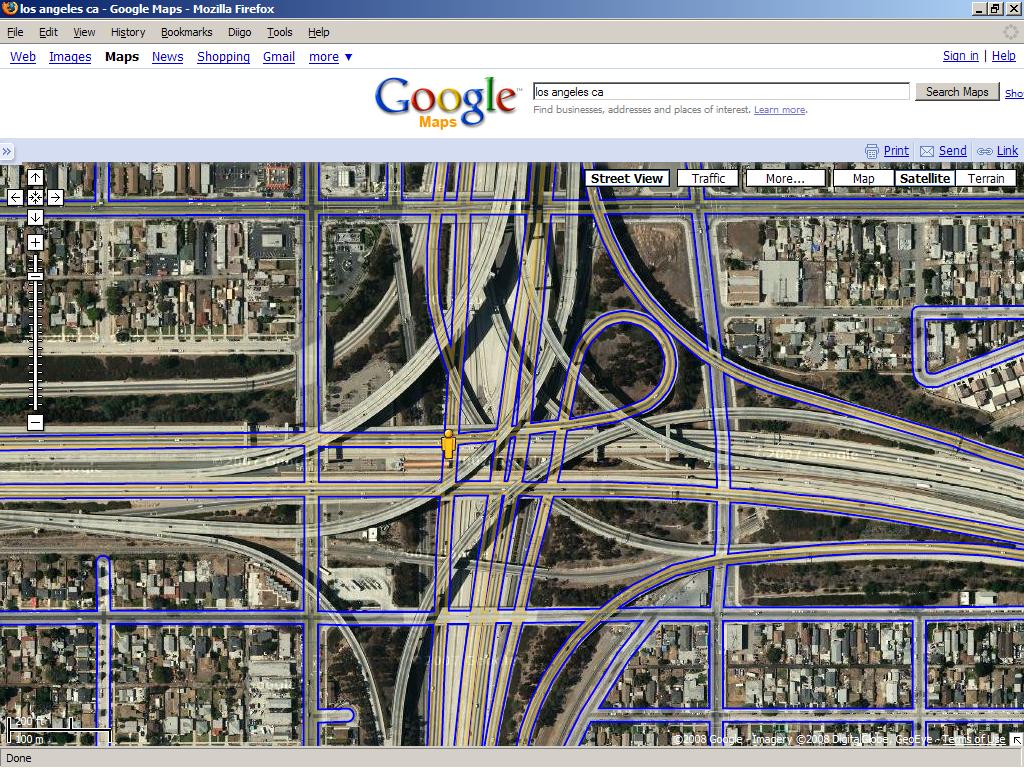

Transportation officials say residents want it both ways. Everyone wants roads that are quick and congestion-free as long as those roads don’t run in front of their homes. Instead of citylike street grids that distribute traffic evenly, suburban developments in recent decades have emphasized cul-de-sacs and winding streets that go nowhere and lacked through streets that could be used by outsiders.

That, said Ronald F. Kirby, transportation director of the Washington Council of Governments, forces almost all traffic onto arterial roads, which are barely able to handle it, especially during rush periods.

Bogged-down traffic on arteries pushes more traffic onto interstates, which were not designed for local trips. For example, Kirby said many motorists who use the Capital Beltway travel only an exit or two, an indication that regional arteries aren’t doing their jobs.

If only there were some kind of weapon that could take pressure off the through roads, some way of taking masses of people and transporting them from place to place, some tool that could be used to transform land use patterns…

*I usually walked to school on an almost straight line, right past the barricades. When my parents drove they took the side streets. When I took the bus I walked up or down the block to one of the main streets.